As the saying goes: always read your wine label before popping the cork.

Okay, so maybe we made that one up, but would you buy groceries without reading the label? Or order meal out without looking at the ingredients? Of course not. (Unless you enjoy living life on the edge.) As with any indulgent purchase, reading the finer details will ultimately help you to make better choices.

You can learn a lot from a label. Especially if you know what you’re looking for. But it’s also important to understand what the label isn’t telling you.

So, how do you read a wine label?

7 things to read on your wine label

In this blog, we’ll be teaching you the seven components of a wine label that you should be looking out for.

1. Country and region

Most wine labels will showcase the produce’s country of origin, either at the top or the bottom of the label. If this country isn’t obvious, it may in fact be because the producer has chosen to display the wine region instead.

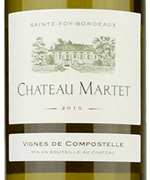

For instance, this bottle of Château Martet displays its region (Sainte-Foy-Bordeux) at the top of its label. Knowing your regions will ultimately help you to distinguish the quality of the wine.

However, don’t get suckered in by grandiose regional labels. ‘Grand Vin de Bordeaux, for example, isn’t a protected or legally-defined term. Any old producer in Bordeaux can slap that on their label to make their wine look more impressive than it is.

The good rule of thumb is that the more specific the location label, the most expensive the wine is likely to be and – we hope – the better it will be. So, a Grand Cru wine from the super-prestigious Le Montrachet vineyard in Burgundy will be labelled ‘Le Montrachet’ and will command a far higher price than generic ‘Vin Blanc de Bourgogne’ blended from vineyards across the region.

Here’s another important tip. English wine – including some premium sparkling wine – is made from grapes grown in England. British wine is a low-price product fermented in the UK from imported concentrated grape must.

2. Name and/or producer

Similarly, the name of the wine producer will be displayed on the front of most bottles, too. Unless you’re a keen wine geek, this might not mean much to you. But each producer will bring their own expertise and uniqueness to their products.

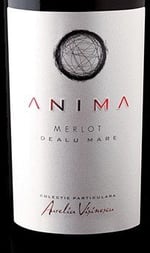

At the bottom of this Merlot, you’ll see ‘Aurelia Visinescu’, one of our favourite producers, displayed clearly on the bottom. A producer may be a family, a business, or an individual wine enthusiast.

Estate bottled wine tends to be better quality than wine made on a larger scale by a négociant. This is because the person growing the grapes is also making the wine and most likely cares more about the quality of the output. Look for phrases like ‘Mis en Bouteille au Château’.

3. Variety of grape

Using the example from the previous point, we can see that the bottle clearly displays the variety of grape (‘merlot’) used in production. Of course, depending on the grape, this will indicate the tasting notes and depth of the wine.

If your bottle doesn’t showcase the grape, it may be that the producer used a blend of more than one grape. In this case, look for the appellation. This can give you an idea of what grapes might have been used within the bottle, as per the regulations for that region.

Unfortunately, many bottles don’t show the varietal on the front label. For example, the French just assume you know that white Burgundy is almost certainly made from Chardonnay and red Burgundy is made from Pinot Noir. You may get some help from the back label. New World wines are more likely to be varietally labelled than traditional European bottles.

Although regulations vary, even if a wine is varietally labelled, it may contain up to 15 percent of a different grape and producers often add a little bit of something else to balance the wine. But they don’t have to tell you if they don’t want to.

4. Vintage or non-vintage

Look out for the year the wine was produced on the wine label – this is called the ‘vintage’. If it’s not immediately clear on the front label, take a look on the neck of the bottle or on the reverse side.

This year indicates the year in which the grapes were harvested. Vintages vary from year to year. A badly-timed storm during the harvest or hail can turn a promising vintage into a bad one. At the higher end of the market, therefore, the vintage can tell you something about the quality of the wine. Wine from a good year is better than wine from a bad year.

Vintage Champagne and Vintage Port are only released in good years so the very existence of a vintage date is a sign of (hopefully) better quality.

But whatever you’re drinking, the vintage date can help you decide how much ageing the bottle has had. Non-vintage wines are usually ready for drinking on release and are generally unlikely to improve with age.

In some cases, like Rioja, words like ‘Riserva’ and ‘Gran Riserva’ have protected meanings and indicate longer ageing. But in most cases, adding the word ‘Reserve’ on the label is just marketing.

5. Alcohol level

The Alcohol by Volume (ABV) level is useful to know. Red wines hover around 13.5 percent on average and white wines a little lower. You’ll usually find the percentage in a finer print at the bottom of the front or back label. Legally, they don’t have to be more accurate than 0.5 percent one way or another.

You may want to match a lighter wine with lighter food – a Muscadet with shellfish, for example – or a heavier red with steak. There’s nothing wrong, per se, with a wine that has a high 15.5 percent ABV, even if the fashion is now for more moderate levels of alcohol, providing it is in balance with the acidity and fruit in the wine. But a high level of alcohol could point to a jammier, flabbier wine.

In some regions, there’s a maximum ABV limit designed, for example in warmer climates where grapes ripen quickly and the limit is designed to force producers to retain some acidity and balance. In other regions, there’s a minimum ABV limit, for example for some cooler region white wines, like a Smaragd Riesling from Wachau and the intention there is to avoid excessive acidity. Not too hot and jammy, not to cold and acidic; just right!

6. Sulfites

By law, producers must tell you if sulfites were used, if they exceed 10 mg/litre. Most producers use sulphites and some use a LOT. But they don’t have to tell you how much. This can be an issue for people with sulfite allergies. Equally, natural wines that use little or no sulfites aren’t automatically more wholesome; sulfites reduce the risk of bacterial infection and oxidation.

7. Sweetness

Nearly all red wines are dry. This means that the sugar in the grape juice has been completely turned into alcohol leaving levels of residual sugar that are too low for professional tasters to identify. This minimum detection level is around four grams per litre.

Most white wines are also dry but some are deliciously off-dry or sweeter. You’re very unlikely to get a sweet table wine in a pub so instead of asking for a ‘dry white wine’ ask for a ‘Sauvignon blanc’ or a ‘Chardonnay’ and you’ll automatically sound more knowledgeable.

There’s also a myth that German wines are going to be sweet and therefore unfashionable or unpalatable. We love Rieslings at Chateaux Vincarta. While many are technically ‘dry’, they are often have a touch more residual sugar and more fruit sweetness that many people are used to. For dry German wines, look for ‘Trocken’ on the label, which means dry. But if you want sweet look for ‘Auslese’. In Champagne, the words Brut and Brut Nature imply a dry and very dry style, respectively.

What’s NOT on the label

Producers may tell you if egg or dairy products have been used for fining the wine, to make them clearer and brighter. But they don’t have to say anything.

Similarly, they don’t have to say anything about their farming methods. If a wine is labelled as organic or biodynamic, then it must meet those requirements, but cheap plonk is often the result of very intensive farming methods. In particular, we worry about overproduction in Prosecco.

There is no requirement to tell you anything about the other ingredients in the wine – for example the purple dye or oak chips that some low-cost producers use. What yeast was used in the fermentation? Nor is there any requirement to tell you anything about how the wine was made. Was it fermented in a concrete tank from 1970s or an expensive new French oak barrel? You may never know.

Pick the best of the bunch

When you break it down, there’s actually quite a lot of information to digest on a wine bottle label. With practice, and the right research or reading list, or even an introductory course at the WSET, you’ll be able to distinguish the higher quality wines from those that’ll ‘just do’. It pays to choose good quality wine with honest labels from thoughtful producers and, ahem, from retailers who know their Grand Vin from their Premier Cru.

So, why not head to your local wine shop and have a peruse?